Introduction to Information Theory

What is information?

At first, that question sounds almost as ridiculous as, “What is light?” or, “What is air?” We are awash in information, like we are awash in light and air. And we have practical, common-sense notions of what information is. We read and gain information. We watch a TV program or movie and gain information. We have a conversation and exchange information. Information is everywhere, and we give and take it continually.

But information is not nearly as simple and “common-sense” as it seems to us at first glance, and our everyday activities that employ information are actually profoundly involved and complicated. Just as empiricists oversimplify the processes that underlie experience and life itself, they radically oversimplify what information is.

Just as Kant asked the truly profound question, “How is experience itself possible?” we now ask a related question: “How is information possible?”

Defining the Term

It turns out to be harder than you might think just to define the term “information.”

Biologists, for example, love to talk about how information-packed the DNA molecule is. They wax eloquent about how the codon enzymes transcribe DNA sequences according to the “information” contained in the various combinations of the four bases, and the process as they describe it is akin to the formation of a salt crystal: It has a chemical inevitability about it. The various molecules just must “perform their functions” according to the “instructions” given them.

Perhaps this is just sloppy-speak, as the well know that terms like “instructions” and “functions” are not appropriate when talking about the formation of salt crystals; scientists know that there is nothing “inevitable” about the molecular relations and processes in a living cell. In fact, they well recognize that the formation of an inert, lifeless salt crystal is nothing like the functioning we recognize as “life.” Actually, the fact that the DNA transcription process is not wholly-deterministic nor inevitable like the formation of a salt crystal is one of the foundations of evolutionary theory: Mutations must occur, and mutations in one way or another modify DNA, which just means that the transcription process is not “perfect” or a purely deterministic “chemical process.”

A salt crystal’s chemical structure is not “information,” while a DNA molecule is. But why? What is the difference?

The likes of Richard Dawkins love to use computer programs as analogies for how evolution works. And Dennett and others like to compare human consciousness to computer programs. They make these comparisons because the development of life on Earth sure looks and feels like a “guided” process, and we know that human consciousness is information-laden! We also know that computer programs are very guided and information-laden, so these make “good” analogs for biological processes, even though Dawkins and Dennett are quick to point out that in biology there really is no grand “guidance.” They assert that the process is “blind” and entirely unguided. However, in referring to information and “programming” as they do, evolutionists are really helping themselves to a lot of informational content that they actually cannot in principle explain.

An excellent article about what information is can be found here (opens in a new tab/window), and we will quote from and critique parts of it. Let’s see if the following passage helps clarify what information is, particularly biological information:

It is generally agreed that the sense of information isolated by Claude Shannon and used in mathematical information theory is legitimate, useful, and relevant in many parts of biology. In this sense, anything is a source of information if it has a range of possible states, and one variable carries information about another to the extent that their states are physically correlated.

There you go. Information has a range of possible states, and the conveying of information depends upon physically correlated variables. Hmmm…. Perhaps this passage will help:

For Shannon, anything is a source of information if it has a number of alternative states that might be realized on a particular occasion. And any other variable carries information about the source if its state is correlated with the state of the source. This is a matter of degree; a signal carries more information about a source if its state is a better predictor of the source, less information if it is a worse predictor.

Perhaps it is time to note a distinction between so-called “information theory” and information itself. Shannon is trying to use a particular “information theory” to explain information itself. The phrase “source of information” presumes the existence of information in the first place, and the all-important “it” is entirely undefined. Shannon strongly suggests that “it” is physical, so that the “source” can be in any of a variety of physical states. And a “signal” is conveying the “information,” whatever that is, more or less reliably to the extent that somebody/something can “predict” the “state” of the “source” based upon the state of the signal.

The article uses tree rings as an example:

The familiar example of tree rings is helpful here. When a tree lays down rings, it establishes a structure that can be used by us to make inferences about the past. The number and size of the rings carry information, in Shannon’s sense, about the history of the tree and its circumstances.

But this example actually leads to yet more questions. For example, is the “information source” the tree rings, or is the “information source” the state of the climate while the tree was growing? The most charitable approach would be to say that the climate state was the information source, and the tree rings are the “signal” that more or less reliably specifies the “state” of the climate while the tree was laying down rings. So, the tree “conveys” information about climate in its rings. However, now, the notion of “source of information” is maximally open-ended; it means literally “every detail about the way things are.” If we grant that “the state of everything” is “information,” then we have an unassailable notion of “information,” but at the expense of a general account of its possible conveyance.

For example, as the article says:

Despite the usefulness of the informational description, there is no sense in which we are explaining how the tree does what it does, in informational terms. The only reader or user of the information in the tree rings is the human observer. The tree itself does not exploit the information in its rings to control its growth or flowering.

And this passage is getting at the really crucial point, for “information” to truly be information, it must be readable. It must be interpreted and mean something to somebody. And this fact presses directly on the crucial question of what distinguishes genuine information from just the general states of affairs that make upon physical reality.

The physical/biological inferences about information prefer to employ a bare-bones, physicalist notion of “information.” That way they can refer to “blind” processes (a la Dawkins’ “The Blind Watchmaker”) with no “meaning” or “interpretation” at all. So, Shannon’s notion of “information” is considered widely applicable in biology, because it amounts to the claim that “information” is just reality itself. And “information theory” amounts to the “blind” physical processes that “work with” those states of affairs to produce other states of affairs.

However, this notion of “information” is not adequate!

Even if we were to grant that it is an aspect of what “information” is, we know that it cannot be a complete account of what “information” is. We are going to look into why in a moment. However, at this juncture, let’s contrast Shannon’s notion of “information” with another, more “common-sense” definition:

What is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

This definition does not actually define “information” itself. Instead, with the typical focus on information theory, it says in effect: “There is something, the information, and whatever that is, it can be represented by some particular arrangement.” So, for example, a written sentence conveys information by a particular arrangement of letters, words, and punctuation. Still, we have no account of what the “information” is; we know only that there is a way of conveying it, and that way is a particular arrangement. Our “account” now is not explaining “information.” It is instead explaining conveyance.

And all popular definitions of “information” fall into this same trap. They end up appealing to the means of conveyance, which presumes the existence of something that is being conveyed, and they end up vaguely treating what is conveyed as in some way dependent on or closely related to the means of conveyance.

This approach to the question is by design in our deeply naturalistic, empirically-mind society. And throughout the rest of this discussion, I am going to refer to this fundamental mistake as a “category error” that conflates syntax with semantics. (Don’t worry. I’ll explain these concepts as we go.)

Category errors occur when a person conflates one “category” of thing with another to produce a wildly erroneous inference. Consider this conversation:

You: How are you doing today?

Me: Oh, I’m feeling sort of blue today.

You: Blue? Really? What shade of blue?

Me: What? I don’t understand. It’s not about “shades.” I’m just feeling a bit down.

You: Well, you said “blue” so I was trying to get a mental picture of it, you know, like the shade. Sky blue? Ocean blue?

And there you are: Category error. Thought of in one “category” the term “blue” is a feeling. Thought of in another “category,” the term “blue” is a color. Conflating the two categories is a “category error.”

And precisely this sort of category error occurs as empiricists conflate the syntax and semantics of “information” in their various uses of that term.

Whether we are talking about tree rings, a sentence, or an ordering of zeros and ones in a binary pattern, empiricists necessarily equate the information itself with its means of conveyance.

Syntax vs. Semantics

This distinction parallels our “form vs. content” distinction in logic.

In a nutshell, syntax refers to the structure and ordering of a message (such as the grammar of a sentence), while semantics refers to the meaning of the message. Many empiricists use the term “information” in the sense that the semantics just is the syntax. Others use “information” in the sense that the semantics emerges from the syntax. And you will remember these sorts of approaches from our earlier discussion about types of materialism about mind.

Remember that naturalists/empiricists are ultimately materialists. Today, materialism is all the rage, because the successes of physics has made it fashionable to think that everything, literally everything, can be explained in terms of matter. But if matter is all there is, then information is necessarily material as well.

The materialist view of mind has several “flavors,” but they all in one way or another make mind just another material part of the material universe. And materialism about information takes the same approach. “Information,” whatever it is, must somehow “reduce to,” “inhere in,” or “emerge from” some material form of “codification.” Frankly, this means that “information” is necessarily all and only syntactical. According to empirical information theory, in one way or another, once you have “specified” the syntax of the “information,” you have said all there is to say about it.

So, the materialist has an answer to our question: “How is information itself possible?” The answer is: “It is represented by some form of material codification. Once you have defined the codification scheme, you have specified the information.”

Pushing the Question Back a Level

Now, we had asked the question: “How is information possible?” Empiricists answer something like this: “‘Information’ is really just all the (material) facts of reality, and it is conveyed in some ultimately material form via structured messages. Once you have defined the structure, you have effectively ‘picked out’ the ‘information’ that will be conveyed.”

Okay, but keep in mind that we are now really thinking about two things: 1) the information itself, which was the subject of our original question; 2) the means/process by which the information is transmitted or conveyed. Empiricists address the first by saying, “All that exists, all states of affairs can be considered ‘information.'” And they address the second by saying, “Specify the structure of the ‘message,’ and you have defined ‘the information’ in that sense.”

But now their “answer” to the original question is not really an answer. They have really just pushed our original question back one level. We asked, “What is information, and how is it possible?” Given the empiricist “answer,” we must now ask an additional question: “What, if anything, differentiates ‘information’ from ‘non-information’ among all of the states of affairs?”

You see, if literally everything is information, then empiricists are not distinguishing between, say, the “structured” ordering of a salt crystal and the “structured” ordering of a sentence. The former is not ‘information’ in any sense that matters to anybody, while the latter certainly is. And what we are really asking is: “What imbues a ‘message’ with the ‘mattering to anybody’ that is certainly a defining characteristic of genuine information?”

Let’s look at a very compelling example.

Following is a totally random sequence of letters, numbers, and other characters. Please take my word for it that this sequence is as random as can possibly be generated (based upon a very, very sophisticated computer algorithm for producing just such purely random strings of characters).

kDELMAkGA1UEBhMCR0IxGzAZBgNVBAgTEkdyZWF0ZXIgTWFuY2hlc3RlcjEQMA4GA1UEBxMHU2FsZm9yZDEaMBgGA1UEChMRQ09NT0RPIENBIExpbWl0ZWQxNjA0BgNVBAMTLUNPTU9ETyBSU0EgRG9tYWluIFZhbGlkYXRpb24gU2VjdXJlIFNlcnZlciBDQTAeFw0xNDEyMTgwMDAwMDBaFw0xODAxMTAyMzU5NTlaMGQxITAfBgNVBAsTGERvbWFpbiBDb250cm9sIFZhbGlkYXRlZDEdMBsGA1UECxMUUG9zaXRpdmVTU0wgV2lsZGNhcmQxIDAeBgNVBAMUFyouY29uY2x1c2l2ZXN5c3RlbXMubmV0MIICIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAg8AMIICCgKCAgEAvR7qxDp22ggl2GQaGTyGepZpS4mqQw9ArPTtR2tNMIDFtPzvmD18I/LF+hP5+kZ57TTleKKGeHXs/QiWkJGoXCNK1zsUbDm8X2UG+gSfRdijtkEVyr/fWwnAhrh12UbQtm8opA5GZXV/zroQWHZ/mC2mtO6YcK6WRS/7lTJrMfD/UILh460UYOjYDARFbCCKzJkIUdmnrZ/dMOsmzoCcpziQawZkq1zT

Now, here is the huge question: “Is this string of characters ‘information?'”

Empiricists will say, “Well, it’s a state of affairs in the universe, so, yes, it’s ‘information.'”

But that is the wrong answer, because pure randomness is not on the face of it valuable or “content-laden.” It doesn’t mean anything to anybody. This string of characters has neither syntax nor semantics! So, nothing is being conveyed by this “message” at all. The empiricists’ “answer” to the pressing question cannot distinguish between genuine information that means something and the “information” that is just the “background noise” of all of the states of affairs in the universe.

This fundamental point about “background noise” is made all the more compelling when you think about, say, the SETI project (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence). One of the major features of the “search” is that SETI employs huge radio telescope arrays to monitor the radio signals reaching the Earth from huge swaths of the universe. SETI captures vast quantities of data across the radio spectrum and uses supercomputers to analyse this data looking for patterns. You see, patterned data suggests informational content which implies intelligence. SETI very intentionally differentiates between random “noise” and genuinely patterned data. The former is not “information,” while the latter just might be. SETI thus does not actually accept the general empiricist “answer” to our question, as SETI recognizes that random “noise” is not “conveying anything.”

So, empiricists really have pushed the question back one level with their “answer,” and SETI itself depends upon the need of a better “answer” than is the general answer empiricists give. “Information,” whatever it is, is certainly not “all of the states of affairs in the material universe.” SETI is looking for genuine information that means something to somebody, where that “somebody” just might be alien intelligence. Pure randomness is not construed to mean anything! And that is to say that meaning matters in information. Syntax alone does not define information, nor can it. Syntax is a necessary but not sufficient condition for information. And somehow you have to get from form to content, from syntax to semantics, because genuine information has semantical content; it means something to somebody. Whatever information is, it is imbued with intentionality!

To really see this point, consider the following example.

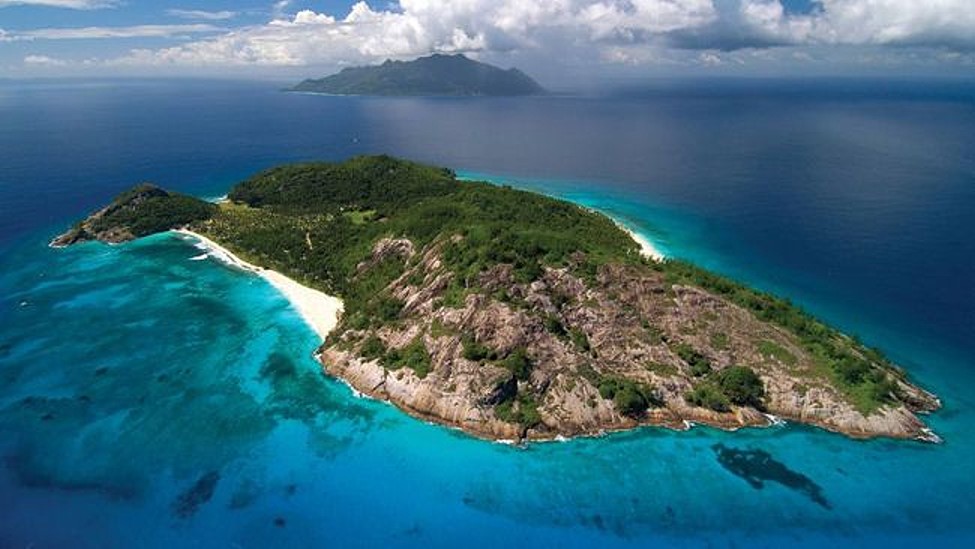

You are flying over an island one day, and you see this….

Now, you see nothing unremarkable here and keep flying.

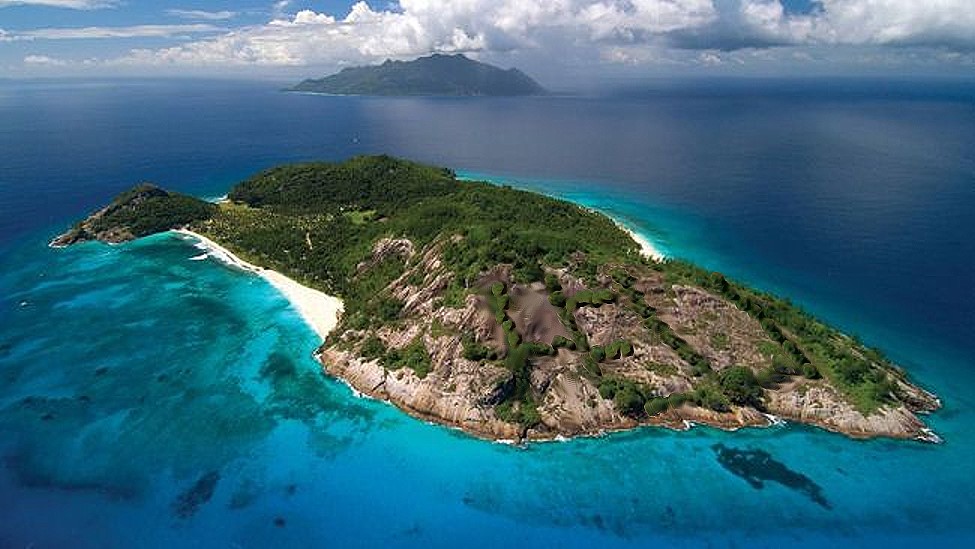

Several months later you fly over the same island. But the second time you you see this….

Now, look more closely, and you see that a pattern of growth has formed. It appears to spell out the letters H E L and perhaps the start of a P.

At this point some questions occur to you that did not enter your mind several months earlier.

* Is there an obvious natural explanation, or does this emerging pattern signify somebody attempting to send a message?

* The P is only starting, if indeed that is what it is. So is the missing P an indication that this is really not a message after all, or does it mean that whoever is crafting the message is not finished?

* If this is indeed an unfinished message, is that a P forming or an L or something else?

* What if it is designed to say “HELP”? Should we immediately investigate or wait for the message to be finished?

And so on.

But notice that the comparison between the two views of the island raises questions that would not emerge if you had only seen the first view of the island! And the entire reason that such questions emerge concerns the contrast between obviously random growth on the island and what appears to be significantly patterned growth in the second view. Pure randomness does not immediately signify information, while patterns immediately make us at least wonder if information is being conveyed.

Of course, there are patterns that we don’t take to be “information,” such as the structure of snowflakes or salt crystals. But patterns are immediately interesting in a way that randomness is not. So, what makes the difference in our minds when we see information in some patterns but not in others? The key distinction is intentionality.

In the first fly-over of the island, we see no evidence of intentionality. In the second fly-over, the pattern of growth is certainly consistent with intentionality. We have to at least seriously consider the possibility that somebody is stranded down there and has spent time attempting to arrange things to express a message: HELP. And we are motivated to investigate further in the second case, while we are not in the first. We want to know if what we see is genuine information, and the only way to find out is to see if we can find some intentionality behind the pattern.

That intentionality, expressed in semantical content, is the foundation of information. So no “account” that cannot account for this intentionality is no account at all! Any empiricist that helps themselves to “information” while denying the crucial aspects of what information is (even as understood by SETI) has gone far beyond merely “oversimplifying” the issue; they have abandoned any serious attempt to answer the question.

Thus, any possibly adequate account of what information is and how it is possible must give an explanation of semantics and intentionality.

Back to the Original Question

So, we are back to our original question, but now with a better understanding of what a genuine answer must include. A genuine answer must distinguish between “background noise” and genuine information, and it must do so by accounting for the intentionality and semantical content that genuine information has.

In short, rocks are not intelligent, do not possess intentionality, and therefore do not naturally contain nor can convey information. By sharp contrast, people are intelligent, do possess intentionality, and therefore do naturally contain and can convey information. Rocks are not naturally information-laden and have no means to convey information, but people are information-laden and have the means to convey information. We are trying to understand what differentiates rocks from people regarding these innate features. What exactly do people have that rocks lack in terms of information?

To further pursue that question, let’s again consider the random string of characters from earlier:

kDELMAkGA1UEBhMCR0IxGzAZBgNVBAgTEkdyZWF0ZXIgTWFuY2hlc3RlcjEQMA4GA1UEBxMHU2FsZm9yZDEaMBgGA1UEChMRQ09NT0RPIENBIExpbWl0ZWQxNjA0BgNVBAMTLUNPTU9ETyBSU0EgRG9tYWluIFZhbGlkYXRpb24gU2VjdXJlIFNlcnZlciBDQTAeFw0xNDEyMTgwMDAwMDBaFw0xODAxMTAyMzU5NTlaMGQxITAfBgNVBAsTGERvbWFpbiBDb250cm9sIFZhbGlkYXRlZDEdMBsGA1UECxMUUG9zaXRpdmVTU0wgV2lsZGNhcmQxIDAeBgNVBAMUFyouY29uY2x1c2l2ZXN5c3RlbXMubmV0MIICIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAg8AMIICCgKCAgEAvR7qxDp22ggl2GQaGTyGepZpS4mqQw9ArPTtR2tNMIDFtPzvmD18I/LF+hP5+kZ57TTleKKGeHXs/QiWkJGoXCNK1zsUbDm8X2UG+gSfRdijtkEVyr/fWwnAhrh12UbQtm8opA5GZXV/zroQWHZ/mC2mtO6YcK6WRS/7lTJrMfD/UILh460UYOjYDARFbCCKzJkIUdmnrZ/dMOsmzoCcpziQawZkq1zT

Do you detect anything there yet? I keep referring to it, so it must be important.

Okay, let me save you minutes to hours of fruitless scrutiny! The string is truly and absolutely random. You are not going to discover anything by contemplating the string of characters itself.

However, here is a hint to the informational content “hidden” there. In fact, its very randomness is the basis of its tremendous value!

Contrary to what SETI thinks or what empiricists believe, this randomness itself conveys very intentional information! And, ironically, the value of the information depends upon its absolute randomness. There is no syntax to this message! It has no form or structure. It is very intentionally syntactically randomized.

Notice my emphasis on the word “intentionally” in the above paragraph. The message is both syntactically and semantically random. However, it conveys information nevertheless. And the information it conveys is literally the intention behind how it was generated.

Let me explain what this random string really is, and the pieces of this puzzle will start falling into place.

This random string is a portion of my company’s SSL public key for a number of our websites. Without immersing you in technical details, suffice to say that if you visit certain of my company’s websites, your browser will kick into HTTPS mode, which means that it is employing an encryption protocol called SSL (Secure Sockets Layer). The SSL/TLS protocol is the encryption protocol used to protect all sensitive transactions on web sites around the world. Your online banking, credit card purchases, and even signing up for Obamacare are all protected via the encryption protocol that is SSL/TLS.

Again, not to bore you with the technical details, but in essence, the web server and your browser engage in a “handshaking” routine when you first connect. And the routine is a “key exchange” in which both ends of the “conversation” assure each other that they are who they say they are. Once this “handshaking” is complete, both the web server and your web browser are confident in two crucial aspects of this form of security:

1) The web server is who it says it is.

2) All information exchanged between the two ends are “point-to-point,” so that only the two ends of the conversation can see the information in plain-text.

For our purposes, (2) is the most important. When you submit your credit card information to a website, you need to know that nobody else along the Internet pathways can intercept and use that information. You need to know that only the company you are doing business with can see your actual credit card information, and everybody else on the Internet sees only randomized gibberish!

And this is where the encryption “keys” come into play. The web server, for example, is telling your browser: “Here is my public key. With this, you you can know how I encrypted the information on my end, so you can decrypt it on your end.” And the SSL algorithm itself knows how to employ the server’s public and private key to encrypt the information. In turn the SSL algorithm in your web browser knows how to employ the public key to decrypt the information and thereby present it to you in plain text.

Now, here is the kicker! Any particular packet being sent between your web browser and the server (or vice versa) will be totally randomized, just as are the keys themselves. If you are not party to the conversation, and you “sniff” packets during transmission and capture them, all you will see is random gibberish. The keys are random gibberish, and the messages encrypted using the keys are random gibberish. All there is to the entire process is random gibberish… except for the protocol itself! The protocol provides the intentionality and the “rules” by which the randomness comes to mean anything!

Some Implications

Where are we so far? Well, we are trying to define what information is and how there can be any of it. And here are some things we have discovered so far.

Absolute randomness can be meaningful and convey information, as long as it is guided by intentional rules (SSL example).

The lack of randomness, apparent patterns, is not necessarily meaningful nor does it necessarily express information (island example).

So, syntax alone cannot ensure semantical content, nor can the absence of syntax ensure the absence of semantical content.

Information must have both intentionality and semantical content. These feature of information are truly what distinguish it from “background noise.”

SETI might be entirely wrong-headed in its “listening” approach to radio signals. So far, everything extraterrestrial they are getting is apparently random background noise that is apparently without informational content. But perhaps this randomness is really like the randomness of SSL keys and packets! Perhaps SETI has been getting genuine messages all along but simply has not recognized them as such because they have not discovered the encryption protocol that the aliens are using. Maybe the aliens will only bother to converse with another species that is sophisticated enough to learn how to decrypt their messages!

So, information is what it is because of interpretational rules (like the SSL protocol) that define what the syntax even is, coupled with the intention of a sender to send a message according to the rules. Every natural language (such as English or French) defines the syntactical rules. And that enables the language to convey the semantical content intended by the sender.

Without the pre-arranged syntactical rules, all forms of conveyance fail to contain or convey information; they are truly random gibberish. Thus, the rules logically precede the information itself. There is no information without there first being syntax. There is no content without form. As Kant said, “Concepts without intuitions are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.” The corollary regarding information is: “Syntax without intentional semantics is empty; intentionality without syntax is blind.”

Thus, information is: Semantical content intentionally formed and conveyed according to syntactical rules.

Once the rules are publicly known, all sorts of conveyances can be used to send a message.

Information necessarily means something to somebody, and for that meaning to be conveyed to somebody else, the sender must intend to convey according to the rules, and the receiver must “decrypt” according to the shared rules.

Thus, there is no information without intelligence (just as SETI recognizes), and that intelligence is defined as such partly in terms of the syntactical rules it knows and employs.

It is not the case that the materialistic/empirical account is adequate, nor can it ever in principle be adequate. Just as empiricists help themselves to “experience” without asking what non-material features necessarily underlie all experience, they help themselves to “information” without asking what non-material features necessarily underlie all information.

Next week, we will look at these non-material features of information in some detail and thereby explain why empiricism/naturalism will forever and in principle fail to account for the existence of information and the means by which it is transmitted.