Philosophy of Mind Continued 3

We have briefly introduced and contrasted Humean empiricism and Kantian transcendental idealism. We’ve talked about primary and secondary qualities, and we’ve talked about how that division leads to the Kantian division between “things in themselves” and “appearances.” At this juncture, please notice that Kant brings what Locke would call primary qualities “into us,” so that even space and time are more like Lockean secondary qualities. Even space and time are not “in the things,” really. Space and time are aspects of objects that we contribute to the objects.

So, Kant turns the empiricist relation between the world and our ideas on its head. The empiricist argues that our sensory impressions emerge from the world, and our ideas emerge from those sensory impressions. Kant argues that our “sensory impressions” are heavily “massaged” by pre-processing before they ever become anything for us. We have no “raw” sensory experiences. By the time we have a sensory experience, it is already affected by processing that is far “underneath” what the empiricists imagines “sense experience” to be. So, we don’t “wait on the world” to passively receive “sense experience,” as the empiricist says. Instead, we actively “massage” the world to have certain features, and then our experiences all necessarily have those features.

On Kant’s model, what is the nature of this “pre-processing”?

The Faculty of Intuition vs. the Faculty of Understanding

Kant argues that “having an experience” involves two “pre-processing” faculties in us. The first concerns sensation, which Kant calls “intuition.” The second concerns concepts, which Kant calls “understanding.” Of course, we have a completely different sense of what “intuition” means today. And when we say “understanding,” we don’t imagine a faculty that is “pre-conscious.” (Kant does not mean “sub-conscious!”) In both cases, Kant is referring to contributions we make prior to all experience, so both of these faculties operate a priori! We have experiences only after these contributions are added.

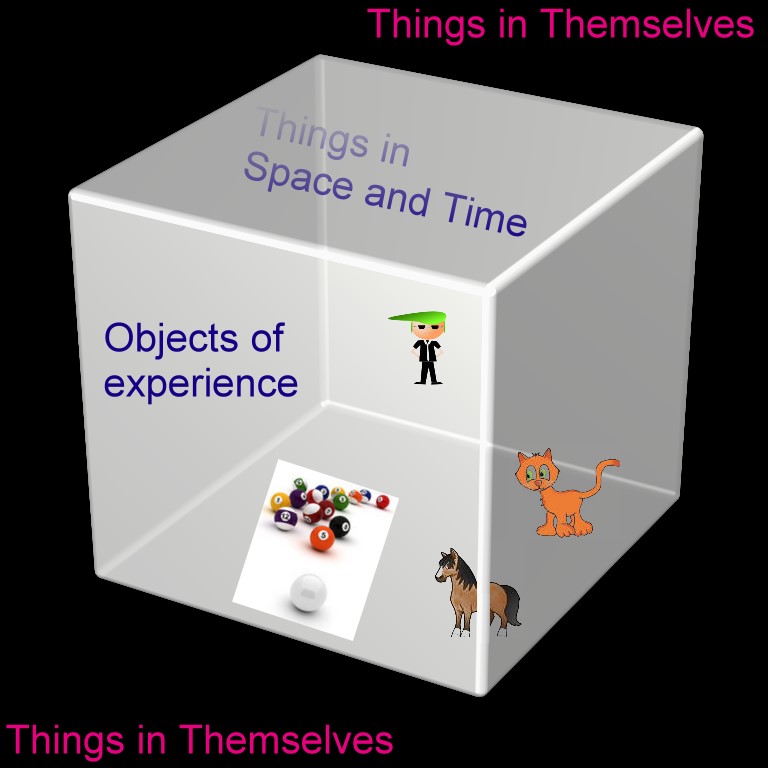

There is no way to perfectly diagram what Kant has in mind, so at risk of being ridiculously inaccurate, I offer the following with explanation:

Things in themselves are not “bound” as this picture has edges and limitations. But imagine it this way: “You” are “immersed” in a boundless realm of things of themselves. You can neither imagine the realm itself nor the “things” that populate that realm. However, “you” receive “input” from things in themselves.

Before that “input” is anything “for you,” that “input” flows through your faculty of intuition, just as light waves flow through the lenses of your eyes before they are ever detected by your nerves and converted to signals in your brain. Just as your eyes’ lenses passively “contribute” to the image you ultimately receive (for example, by flipping “reality” upside down), your faculty of intuition “massages” the “input” from things in themselves by “flipping” them into space and time. Now you have actual sensations, what Kant calls “intuitions” that are ready to be made into objects. They are not objects yet! But they have the forms of intuition, which is the first necessary feature that all objects of experience must have.

Those intuitions are then processed by the understanding, which contributes the a priori forms of apperception, which Kant calls the “categories.” These “categories” include substance, causality, continuity, and other formal relations; Hume could give no account of these features of objects, as he rightly realized that they could not be derived from our experiences. So he called these ideas “fictional.” However, Kant recognized that the reason why all of our experiences are, for example, causally related is not because we get the idea of causality from the objects, as Hume (the empiricist) insisted. Instead, even before an intuition can be an object for us, we “categorize” it causally, so that by the time it is an object of experience for us, it is already a causally-affected object.

So, the understanding “packages” all intuitions (that are already now spatio-temporal) into “categories” before the results are ever presented to us in consciousness. Thus, by the time we can ever become aware of an experience in any sense of the word “aware,” the objects of experience have been “filtered” into space and time, and they have been “packaged” into the forms of the “categories.” We don’t wait on our experiences to see if they are “substantial” and causally-related, as Hume said. Instead, we cannot have any experience that is not of substances that are causally-related!

Thus, our most “substantial” empirical ideas are not derived from the objects of experience! Because of the a priori filtering and processing prior to all experience, it is necessarily true that all experiences are spatio-temporal and “substantial,” causal, etc. Two faculties, intuition and understanding, work in harmony “in us” to produce the objects of experience we have and that emerge for us from the “input” of things in themselves.

Because of all this a priori filtering and processing, the objects of empirical experience are all and always of appearances! We never can know what things in themselves are like, what Kant calls “the undetermined.” All we ever can know are objects of experience (empirical objects), and these all necessarily come to us as “appearances” after the faculties of intuition and understanding have “had their way with” the data of things in themselves. Thus, we truly do “live in a box,” and what is outside the box is entirely unknowable in principle by us!

Concepts are empty; intuitions are blind

Kant famously (and most often misunderstood) said: “Concepts without intuitions are empty, and intuitions without concepts are blind.” What he means, in a nutshell, is first this: The faculty of understanding is purely formal.

Pure concepts without intuitions have no content! Remember our form vs. content distinction from early in this seminar? Think of a logical relation such as this one:

P ⊃ Q

P

———–

Q

You recognize this as the always-valid inference called Modus Ponens. But what is it saying? What does it mean? Is the conclusion true or false?

You cannot answer any of these questions, because such answers would require you to plug content into that form, such as this:

If it is raining, then the streets are wet.

It is raining

———–

The streets are wet.

This inference is in the form of Modus Ponens, but now Modus Ponens has been given content! Now it means something. And now you can know that (as I write this) the conclusion is true!

The a priori forms of the faculty of understanding have no content. They are empty! They are waiting to receive input from the intuition, but until they do, there is nothing to “structure” into the forms.

By “intuitions without concepts are blind,” Kant means the corollary of the previous principle. Unlike the previous example, we cannot even imagine what un-formalized intuitions could be like. By the time we ever become aware of our intuitions, they are already “formalized” by the understanding. And this is Kant’s point. Intuitions that have not been “formalized” by our understanding are nothing to us; we are “blind” to them!

The a priori work of the understanding is like a computer processor that is just waiting to process data and produce output (the objects of experience). However, until it gets data to process, it just waits. No input; no output! The computer screen is blank, because the processor has nothing with which to work to put anything on the screen.

The pre-processed intuitions are like data that have not yet been sent into the processor. The computer screen is blank because that data has not been processed into any form that can be represented on the screen.

In both cases, you have a blank computer screen. The only way to get something onto the screen (to be empirically aware of any object of experience) is to get the data of intuition into the processor of the understanding. As soon as data is processed, the screen lights up, and objects of experience start dancing across our consciousness!

The Mind as a Stream of Consciousness

The empiricist/materialist notion of mind is that it is nothing but a stream of brain states or a stream of empirical experiences that can be “reduced” to a series of brain states. But we are now seeing the fundamental problem with this perspective.

The brain is itself just an object of our experience, as are its states. In fact, absolutely everything that empiricists refer to and that scientists can measure are all empirical objects. But before we can be aware of any of those things, because we can “do science” on any of them, a very complex series of filtering and processing had to take place. And that filtering/processing could not have taken place “in the brain,” because there could be no brain to measure and scientifically analyze prior to that filtering/processing sequence. By the time science is talking about “brain states” and trying to correlate a pain to a brain state, the “pain” is already an “object of experience,” and the brain is already an object of experience. Science cannot get “deep enough” fast enough to “capture” the pre-processing that underlies all experience.

For there to be empirical experiences at all, even of ourselves looking inward, the a priori filtering/processing has already taken place, and we can never “see” or “be aware” of that filtering/processing happening because it occurs a priori! So, all of what we know, even of ourselves, necessarily depends upon the a priori activities of faculties that we can derive as “working” but that we can never “experience.”

This means that whatever model of “the mind” empiricists dream up, they are never really knowing what we are in ourselves. There is something that is “us” that underlies our empirical selves. And that something will always and necessarily be beyond the reach of scientific/materialistic investigation and explanation.

The Soul

Now we have the barest explanation of what could be called the “soul,” that “something in itself” that is forever beyond our explanation. Kant called the “processor” the unity of apperception, and there is so much more we could say about this in a dedicated Kant seminar!

But, remember, that unity of apperception is “empty” without the data of intuition that itself depends upon “inputs” from the body in some way. Take away the body, and the “inputs” of the intuition cease. And the unity of apperception without intuitions is empty. It is not “conscious.”

So, in death, the soul (unity of apperception) “sleeps” unconsciously. It has “nothing to do,” so it has no objects of experience to produce and “display” to “be” conscious experiences. Well does the Bible say, “The dead know not anything.” And that is because “knowledge” is intuitions plus the operations of the understanding. Take away either one, and you have no “experiences” at all.

What is the “second death” in the Biblical sense? You are probably already seeing the answer! The second death is when the now-unconscious soul (which is itself an object of experience in God’s mind) is simply forgotten by God; it ceases to be an “object” for God among the things in themselves that is His realm of direct experience. Prior to God “forgetting” your thing in itself, it can always be conjoined to some mode of intuition, which then supplies data to the understanding, which produces a conscious being. Death eliminates that data of intuition, and the understanding falls unconscious. And when the understanding in itself, that unity of apperception itself, ceases to exist as an object of God’s “experience,” that being completely ceases to exist and the “second death” from which there is no possible resurrection can be said of it.

Knowing as we are known

This verse in 1 Cor. 13:12 is one of the most intriguing in all of Scripture: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

I believe that no violence is done to Paul’s actual intentions to recast that verse this way: “Now we see through space/time & categories, darkly; but then face to face with God: now I know only the appearances; but then shall I know what I now cannot even imagine.”

Whatever our “glorified” bodies will be like, we can be confident that they will provide different forms of intuition (perhaps giving us access to many other dimensions and “times” of experience) that are entirely unimaginable to us now. And we cannot even imagine the beings that presently “know” us but that we cannot “know” because we are at present in a completely different “box” than they occupy. What would it be like to be “as are the angels” in every sense? We are talking here about entirely different planes of existence than we can possibly imagine. And this is why 2 Cor. 4: 17-18 is all the more exciting when thought of in Kantian terms: “For momentary, light affliction is producing for us an eternal weight of glory far beyond all comparison, while we look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen; for the things which are seen are temporal, but the things which are not seen are eternal.”

We are not just looking forward to “happy times” in a “neato kingdom.” We are looking forward to seeing as angels see, experiencing much closer to what God Himself experiences, in which space means something completely different and when “time shall be no more.” That is not metaphorical talk, once you understand Kant!

Many verses refer to the great reward of Christians, and when interpreted in Kantian terms become not vague metaphors but instead tangible promises that we shall be taken out of this present “box” and placed such greatly expanded boxes of experience that our experiences then are beyond our imagination now. But such experiences will be as real to us then as our present experiences are to us now… just vastly more empowering! And we will know God then as we cannot even imagine to know Him now!