Evidence

Everything we have discussed so far in this seminar has been leading to this first fundamentally significant point: We must carefully assess evidence in our decisions of what to believe. We are perpetually assessing evidence, so one of our most fundamental goals in this course is to sharpen both that assessment ability and the recognition of what evidence even is.

When most people think of evidence, they think first of something like a court case. They think of witnesses, physical evidence, psychological evidence, and so on. So, when reading about Clifford’s notion of “sufficient evidence,” most people imagine a “weight of evidence” in the sense of legal definitions, such as “preponderance of evidence” or “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

However, Clifford has a deeper notion of “evidence” in mind, and in this course we will go even deeper. We are going to focus primarily upon types of evidence in a sense that gets underneath the majority of what most people think of by the word “evidence.” We are going to take this deeper look because the biggest confusion in arguments between science and religion concerns what “evidence” really means. Here is a subject where philosophers can contribute some important clarification.

To properly consider evidence in a rigorous, philosophical sense, we must first get clear about two Latin terms: a priori and a posteriori. These terms are actually easy to remember if you look at the terms “prior” and “post” in them. We know that “prior” means “before” and “post” means “after.” And that is the clue to interpreting these terms. A priori refers to “prior,” and a posteriori refers to “after.” But before and after what?

What you will discover by reading this post about a priori and a posteriori knowledge is that “before” and “after” are relative to sensory experience. A priori knowledge is gained apart from experience, while a posteriori (also called empirical) knowledge must be gained through experience.

A priori knowledge is utterly reliable, because it is necessary and universally true. By contrast, empirical knowledge is unreliable, because it is contingent and relative.

Now, these two mutually-exclusive types of knowledge are the basis for the most basic and long-standing divide in philosophy: rationalists vs. empiricists. And the philosophers debating the merits of their chosen side of the divide ultimately produced the Enlightenment… the implications of which are with us to this very day!

So, it behooves us to understand (at least in nutshell) the rationalist/empiricist divide, because in many ways it parallels the religion/science debates of our present day. Please read this post for an overview of rationalism vs. empiricism.

In order to really tease out what “camp” a given bit of evidence is in, let me provide (with apologies to John Locke) a “Lockean Model of Knowledge” that I think is an accurate and very revealing representation of how “evidence” can be categorized and analyzed.

Before I present some diagrams, however, it bears mentioning why it is important to properly categorize types of evidence the way I do.

Let’s imagine that you tell me something like this: “I just saw a terrible accident, and three people were killed, I think.”

I respond, “Really? Terrible indeed! Three people, you say? How do you know it was three people and that they were killed? Did you measure their sides to be sure that the Pythagorean Theorem substantiates your perspective of what happened?”

Uhh… nutty! Right?

This sort of odd comparison is what we call a “category error.” The Pythagorean Theorem is not the tool (or method) I should employ to assess the evidence you presented!

What I’ve done wrong in my “assessment” is not only that the Pythagorean Theorem applies only to (Euclidean abstract-object) right triangles. That would be bad enough! But my “assessment” is even more confused: you have presented empirical evidence, and I am trying to assess that evidence in strictly rationalist terms. So there are (at least) two category errors in my “assessment.”

When we assess evidence, there is nothing more critical to accuracy (and charity) than that we properly categorize that evidence. Only then can we employ the correct assessment tools and methods! So, we will be careful in this very way as we further contemplate the religion/science divide, and in particular as we assess the arguments scientists employ to support evolutionary theory.

You can click on the following diagrams to expand them to full size.

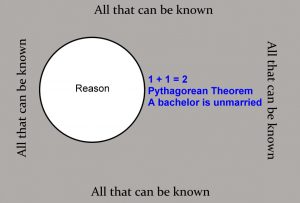

For each of the diagrams, we treat the grey background as “all that can be known.” This approach does not assume anything about whether or not there are things that we in principle can never know. And, keep in mind that we are seeking metaphysical knowledge, which is knowledge about actual reality.

In this diagram, we see that one way we might come to know things about reality is through reason alone. Rationalists would say that reason alone is the only reliable way to do metaphysics, because only reason can penetrate beneath how things appear to discover how things really are. So, really, rationalists could well say that the “reason” circle should encompass the entire grey background, as the only things that can truly be known can be known only through reason. Everything else is “appearances” and deceptive.

In this diagram, we see that one way we might come to know things about reality is through reason alone. Rationalists would say that reason alone is the only reliable way to do metaphysics, because only reason can penetrate beneath how things appear to discover how things really are. So, really, rationalists could well say that the “reason” circle should encompass the entire grey background, as the only things that can truly be known can be known only through reason. Everything else is “appearances” and deceptive.

In this diagram, we see that another way we might come to know things about reality is through sensory experience alone. Empiricists would say that reason alone can never tell us anything substantive and content-laden about the world; reason can only tell us about formal relations. So, empiricists would say that sensory experience is the only possible approach to learning anything substantive about how things really are. So, really, empiricists would say that the “sensation” circle should properly cover the entire grey background, as only through sensory experience can we know anything substantive about reality. So, the only things that matter to be known can be known through sensory experience.

In this diagram, we see that another way we might come to know things about reality is through sensory experience alone. Empiricists would say that reason alone can never tell us anything substantive and content-laden about the world; reason can only tell us about formal relations. So, empiricists would say that sensory experience is the only possible approach to learning anything substantive about how things really are. So, really, empiricists would say that the “sensation” circle should properly cover the entire grey background, as only through sensory experience can we know anything substantive about reality. So, the only things that matter to be known can be known through sensory experience.

In this diagram, we see that yet another way we might come to know things about reality is through divine revelation. Most empiricists and rationalists (today) would claim that this form of “knowledge” is entirely unreliable (even non-existent). However, revelationists would say that there are all sorts of facts about the universe that we can never discover using either reason alone or sensory experience alone. So, revelationists would say that rationalists and empiricists both place inaccurate and epistemological limits upon the discoveries we can make about reality. Revelationists would typically say that the “revelation” circle is properly a subset of all that can be known, as revelationists typically agree that we can know some things about reality via sensory experience and via reason alone.

In this diagram, we see that yet another way we might come to know things about reality is through divine revelation. Most empiricists and rationalists (today) would claim that this form of “knowledge” is entirely unreliable (even non-existent). However, revelationists would say that there are all sorts of facts about the universe that we can never discover using either reason alone or sensory experience alone. So, revelationists would say that rationalists and empiricists both place inaccurate and epistemological limits upon the discoveries we can make about reality. Revelationists would typically say that the “revelation” circle is properly a subset of all that can be known, as revelationists typically agree that we can know some things about reality via sensory experience and via reason alone.

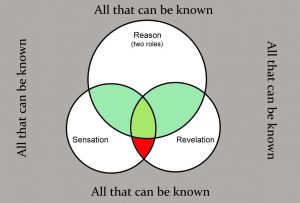

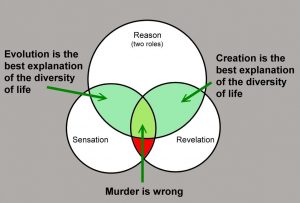

So, let us put these approaches to doing metaphysics together in one diagram, so that we can see how these epistemological categories relate. You will notice that there are overlapping areas among the categories. This is to say that I will argue for an epistemological model in which the “alone” part of rationalism and empiricism is mistaken. As we discuss examples, you will see that reason alone can discover substantive aspects of reality; sensory experience is more reliable than rationalists say it is; and revelation can be demonstrated to be a legitimate way to discover metaphysical facts (this claim is part of the set of conclusions this entire course will draw).

So, let us put these approaches to doing metaphysics together in one diagram, so that we can see how these epistemological categories relate. You will notice that there are overlapping areas among the categories. This is to say that I will argue for an epistemological model in which the “alone” part of rationalism and empiricism is mistaken. As we discuss examples, you will see that reason alone can discover substantive aspects of reality; sensory experience is more reliable than rationalists say it is; and revelation can be demonstrated to be a legitimate way to discover metaphysical facts (this claim is part of the set of conclusions this entire course will draw).

Now, please notice that the “reason” circle indicates that reason plays two roles in metaphysics.

1) Discovery: reason alone is capable of discovering substantive facts about reality. Indeed, the more we know about physics, the more we discover that mathematics is far more than merely a “descriptive language” that can be employed to “model” physical facts. Many prominent physicists have agreed the mathematics seems to somehow actually constrain reality itself, as though “formal” mathematics somehow “reaches across the divide” to literally constrain physical reality. And it is also notable that geometry has this same effect. The Pythagorean Theorem, as just one example, does not emerge from empirical facts but instead constrains them. Empirical right triangles do conform to the Theorem, even though there is no apparent “connection” between formal, a priori geometry and empirical facts.

2) Adjudication: reason also acts as “referee” among metaphysical claims. In this role, reason establishes the “baseline” of metaphysics by establishing the “rules” that may not be violated by metaphysics. For example, an empiricist can never accurately assert that the same door is both open and closed at the same instant. (Quantum theory is a subject that seems to violate classical logic, but that popular perception is mistaken, as we will argue throughout this course as applicable). And even revelation cannot violate logic. God, however He is in Himself, does not seem to be bound by space, time, or logic. But space, time, and logic are among the “boxes” He has placed us in. So, for Him to effectively communicate anything to us via revelation, He must speak to us “in our box.” Thus, metaphysics for us, will conform to reason.

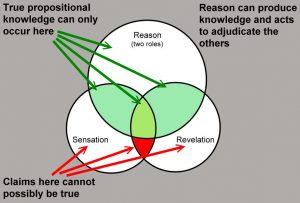

Because reason adjudicates what could even in principle be true metaphysical claims, you see that the “reason” circle constrains the others. Metaphysical claims made by “experience” or by “revelation” cannot possibly be accurate if they violate logic.

Because reason adjudicates what could even in principle be true metaphysical claims, you see that the “reason” circle constrains the others. Metaphysical claims made by “experience” or by “revelation” cannot possibly be accurate if they violate logic.

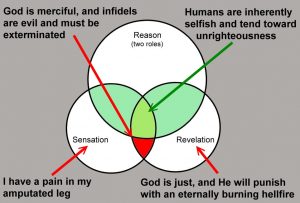

Here we see some examples of claims about reality that would fall into different epistemological categories. Notice the sorts of claims that appear to violate logic and thus would not be true. One might argue that we do not understand God’s justice and thereby try to make the example statement not violate logic. We won’t engage in that particular argument at this moment. But it is a fact that the vast majority of people who think that Christianity is irrational cite this mainstream Christian claim as obviously irrational and as the reason why they reject Christianity. Notice the category denoted in red. This is an area where revelation makes claims that sensory experience would cohere with, yet that violate logic.

Here we see some examples of claims about reality that would fall into different epistemological categories. Notice the sorts of claims that appear to violate logic and thus would not be true. One might argue that we do not understand God’s justice and thereby try to make the example statement not violate logic. We won’t engage in that particular argument at this moment. But it is a fact that the vast majority of people who think that Christianity is irrational cite this mainstream Christian claim as obviously irrational and as the reason why they reject Christianity. Notice the category denoted in red. This is an area where revelation makes claims that sensory experience would cohere with, yet that violate logic.

Within the “properly constrained by reason” categories, we find many claims that could actually be true. Notice that there are claims upon which revelation and empiricism could agree. Empiricists, rationalists, and revelationists would all say that their approach is the only way that a claim like “murder is wrong” can really be substantiated as true! But, at least all would agree that the claim is true. And, there are obviously mutually-exclusive categories of metaphysical claims, as the diagram indicates.

Within the “properly constrained by reason” categories, we find many claims that could actually be true. Notice that there are claims upon which revelation and empiricism could agree. Empiricists, rationalists, and revelationists would all say that their approach is the only way that a claim like “murder is wrong” can really be substantiated as true! But, at least all would agree that the claim is true. And, there are obviously mutually-exclusive categories of metaphysical claims, as the diagram indicates.

There are some important principles that follow from this assessment of epistemological categories. Let us focus on two for the moment:

1) Evidence from one category does not immediately “trump” evidence from another category. Of course, reason in the sense of adjudicator trumps all (as it necessarily must), but in that role, reason is not providing evidence.

2) The trumping of one category by another requires argumentation that must include both how that “trumping” evidence is relevant to evidence from another category (to explicitly avoid a category error), as well as why the “trumping” evidence should be taken to “overrule” the evidence from another category.

The second principle will be interpreted according to bias!

For example, an Enlightenment-minded empiricist would likely say something like, “The Enlightenment showed the vacuous nature of rationalism, and science has shown the intellectual bankruptcy of revelation as an epistemological category. So, empiricism trumps all, and its evidence should win the argument wherever it conflicts with ‘evidence’ from the other categories.”

By contrast, a revelationist would say something like, “The word of God is completely reliable regarding all subjects it speaks to. It is, after all, the word of God. So, wherever evidence conflicts, the other categories must be subservient to revelation.”

And there are some rationalists, even today.

But notice that the actual nature of any conflict between categories is now clearly defined. If you are an empiricist and wish to minimize or eliminate any claimed evidence from revelation, you must argue for why your evidence is relevant to the question and why it should trump evidence from revelation. And, as a revelationist, you have the same task ahead of you.

And here is the most interesting aspect of the relation between the categories: Empiricism is a two-edged sword! As it elevates its own merits, it elevates the merits of revelation at the same time, because revelation is actually a species of empiricism. And as atheist empiricists denigrate the reliability of revelation, they unwittingly attack empiricism in general because the same principled dangers they claim revelation has are shared by science.

Think about how an atheist scientist argues against religion: Religious people are forever accepting empirical evidence that cannot be rigorously tested, such as miracles and sketchy historical ‘evidence.’ Even the ‘evidence’ that they have for the ‘truth’ of the Bible is based upon questionable or even outright mistaken history. Thus, the foundation of their views is empirical but not testable in anything like a scientific way. Their theories are unfalsifiable, which makes them empty. We might as well believe in a few sightings of Yeti. In fact, we are all “atheists” regarding most of the gods that have been worshiped by ignorant people down through the ages. Ra, Zeus, Odin, and the whole litany of others have gone by the wayside, just as will Jehovah. It’s time to be consistent atheists, which means being atheist about just one more god (Dawkins).

Now, consider how the typical Christian argues against atheist scientists: Science is always making mistakes. It is not nearly as reliable as it claims to be. By contrast, I am very confident of the internal experience of God that I have had and continue to have. So, when science asks me to give up my confidence in God’s existence and work inside me, that is like being asked to give up my confidence that I have hands! And I have my own changed life and the changed life of many others as proof of the work God does in people. Furthermore, I find the Bible to be internally consistent and a reliable guide to life. And the Bible provides answers to many questions that science can never touch upon. So, science cannot just claim that there is no judgment or life after this present one, when the Bible assures me of the opposite! And the only eye-witnesses to creation have testified in the Bible, while science can produce no eye-witnesses for its theory of origins.

Both sides are relying upon empirical evidence. Both sides are saying that their empirical evidence is “more reliable” than that of the other side. Both sides conflate pragmatism (what works) with truth. And both sides fail to recognize how fundamentally unreliable empiricism is in principle!

Science cites its chain of “successes” since the enlightenment, and religion cites the civilizing and uplifting influences it has had throughout history.

Science elevates the “scientific method” as epistemologically supreme, and religion responds that creation science should be taught alongside evolutionary theory in science classrooms.

Both sides are like players in those early kung fu movies:

Protagonist 1: My kung fu is stronger than yours.

Protagonist 2: No! My kung fu is stronger than yours.

Protagonist 1: I will have to show you the superiority of crane style!

Then it’s whoosh, whoosh, clack, whoosh, clack… all sound and fury and stylized movements that are predictable in both their intensity and ineffectiveness. And the dance goes on….

Protagonist 1: I see that you have switched to tiger claw technique, but my stabbing crane is still superior.

On and on and on.

In the real world the debates are as predictable, stylized, and ineffective as the old kung fu movies.

The problem in these debates is that both sides are utterly convinced of the superiority of their own method and its resulting evidence, yet both sides fail to see the inherent unreliability in their methods and their resulting evidence. Both sides fail to see the extent to which they are prisoners of hope and faith. And, in this sense, science is, if anything, guiltier.

The vast mistake that religion makes is to try to climb up onto the pedestal it perceives that science has come to occupy. Instead, it should be chopping the pedestal out from under science, showing that science is just one of many legitimate ways to assemble empirical evidence… nothing particularly special, and argue for a sweeping tolerance that must necessarily result from the recognition that empiricism in general is unreliable and its conclusions mitigated by “or so it seems to me at this moment.”

Science is vastly arrogant, drunk by its “successes” and its position of prestige and power. Religion is vastly arrogant, drunk by its spiritual superiority and the sense shared by virtually all it is proponents that it “has the truth, while others stumble.”

In the end, the great divide that emerged from the enlightenment is that between empiricism and rationalism. Empiricism came to be associated with “reason,” and in the minds of many “science” equates to “reason.” Both science and religion are fundamentally empirical enterprises. And rationalism is all but dead. The “modern” period of intellectual history resulted in the elevation of science over religion (called blind faith), with post-modernism nipping at the sensitive parts of both.

As we continue in this course, our goal is to be extremely sensitive to the type of evidence that is under consideration at any given moment. We wish to be charitable, while avoiding category errors. And we will not be wowed by any empirical evidence merely because it emerges from “science.” As we will see going forward, what “science” is and what it actually does is not easy to define and to differentiate from “non-science.”

There are no epistemically privileged positions! Thus, we will argue for an increased humility and tolerance within both the scientific and religious communities, as we evaluate a wide range of metaphysical claims.